How Traceable Threshold Encryption fixed MEV - Part 1

Paper Presentation

The goal of this post is to explain to you the latest research on encrypted mempools to mitigate MEV, miner extractable value. The solution is called Traceable Threshold Encryption (TTE) and it’s a tale of two papers.

The first is by Boneh, Partap and Roten at Stanford University and has been published at the end of 2023. The second is the result from international collaboration including Germany and the UK and has less than a week.

In this post we do a deep dive on the first paper. Next post we talk about the second

History and Context

Here we see a little context, present MEV, Flashbots and mempools, and how Threshold Encrypted Mempools may become a good solution.

Let’s start with the context: We are talking about Ethereum validators and how the ecosystem struggles with MEV. If you don’t know what MEV is, think of it in this terms: Alice submits a swap transaction on Uniswap to exchange 100,000 USDC for ETH. A validator Vlad sees this in the mempool, submits its own transaction with a higher gas fee to buy ETH before Alice. Vlad’s transaction pumps ETH price, Alice’s one pumps it even more. Vlad sells the ETH for 101,000 USDC. Vlad has a profit of 1000 USDC, Alice bought ETH for a less favorable exchange rate.

Companies currently do research to mitigate the problem. One of those is Flashbots and I leave you with a Perplexity brief summary of what it does:

Among the things Flashbots researches, there is a strand of research about encrypted mempools. For those who don’t know, a mempool (short for memory pool) in blockchain refers to a temporary storage area where pending transactions are held before being included in a block.

You can read both Flashbots’ research proposal (source) and the paper they published on it (source), but I can give you the TL;DR in a couple of paragraphs. The rationale behind encrypted mempools is simple: hide information related to pending transactions until a block including the transactions is committed. After revealing the commitment, by definition nobody can change the block. If data is encrypted, no validator can see it and shuffle/introduce new transactions to extrapolate value like Vlad did.

Of course you can not trust a single node/participant to do the encryption/decryption, hence you want to decentralize the handling of the task. Enter Threshold Encryption. Assuming a (previously specified) percentage of honest participants, encryption/decryption is always correct and secure. This prevents frontrunning or similar behaviour.

In summary, Ethereum struggles with MEV, where validators exploit pending transactions for profit. Flashbots has proposed encrypted mempools and threshold encryption to hide transaction details until a block is committed. Goal is to prevent front-running and ensure security through decentralization.

The Problem: Collusion and Data Exploitation

The assumption of honest participants is theoretical. In reality, without a way to trace or deter collusion, businesses face significant financial and reputational risks. This is where Traceable Threshold Encryption (TTE) comes into play.

The need for a “stick” alongside the “carrot” is clear: MEV incentives are so strong that validators might still collude to decrypt transactions early. Even with encryption, this could allow them to front-run others and profit unfairly.

This is because traditional encryption methods focus on ensuring only authorized parties can decrypt data but do not mitigate the risk of collusion, relying instead on assumptions of honesty. TTE takes encryption a step further by introducing a tracing mechanism. If a group of parties colludes to create a decryption algorithm, TTE can identify at least one of the colluders. This capability acts as a powerful deterrent, making collusion far less appealing.

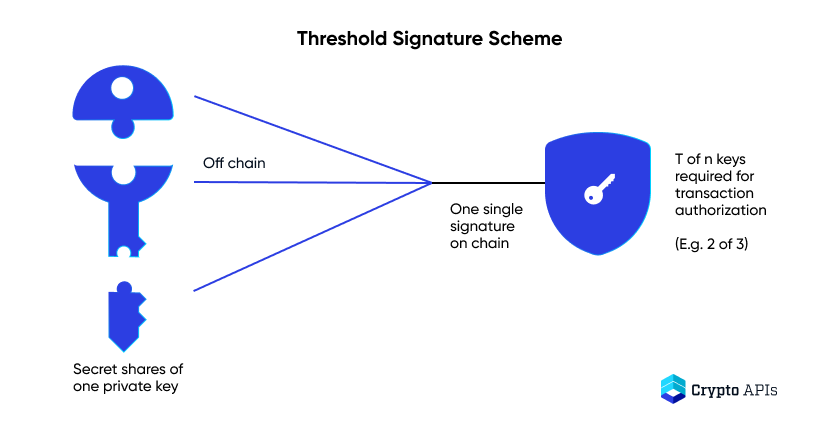

To understand how Traceable Threshold Encryption works, let’s take a step back and describe simple Threshold Encryption. Imagine a scenario where a secret is divided among multiple parties. Each party has a share of this secret. In threshold encryption the secret is the encryption/decryption key. Given an encrypted data, only a specific number of them (the threshold) can work together to decrypt the data, each using its share of the decryption key (read here for more details).

But Traceable Threshold Encryption (TTE) adds a crucial layer: traceability. Here’s how it works in practice:

Key Distribution: Each party receives a uniquely identifiable share of the decryption key.

Decryption: Only when a sufficient number of parties collaborate can the data be decrypted (this step is equal to simple threshold encryption).

Tracing: If a group of colluders creates a decryption algorithm , the system can identify at least one of them by analyzing the algorithm’s behavior.

The tracing relies on the identity, often called "fingerprints," of the decryption keys distributed to each party. If a group of colluders creates a decryption algorithm, the system can analyze the algorithm’s responses to carefully crafted ciphertexts.

By observing how the algorithm behaves, the system can identify patterns that reveal at least one of the colluders, ensuring accountability and deterring malicious behavior. This approach ensures that even if collusion occurs, the system can pinpoint the culprits, discouraging malicious behavior in the first place.

In short, Traceable Threshold Encryption (TTE) enhances traditional encryption by embedding unique “fingerprints” in decryption keys. If colluders create a decryption algorithm, TTE can identify at least one of them by analyzing its behavior, deterring malicious activity and ensuring system security.

Beautiful But Insecure

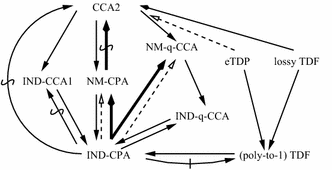

You can classify security in encryption systems as security against Chosen Plaintext Attack (CPA) and security against Chosen Ciphertext Attack (CCA). CCA is stronger than CPA. And. The paper by Boneh et al is CPA secure only, and attacks were done.

It is important to understand the difference between CPA and CCA:

CPA: Even if an attacker can choose plaintexts to encrypt, they can’t distinguish between the encrypted results.

CCA: Even if an attacker can manipulate encrypted data, they can’t gain any useful information from it.

The problem with Boneh et al.’s version of TTE was that they only achieved CPA security. This is how you can attack the system.

Assume you have an encrypted block of transactions. With CPA security in place, and without the decryption key, you can’t directly ask other parties to decrypt the block without revealing malicious intent (as explained in the previous section).

Instead, you can request decryption of slightly altered versions of the message. Even if this reveals malicious intent, it only does so on meaningless data, as the alterations are random. As a result, your behavior is not penalized, allowing you to repeat this process as many times as needed without consequences.

By repeating this process enough times, you can eventually derive the entire decryption key. Without CCA security, CPA security alone allows you to manipulate encrypted data and extract useful information, exposing the system to potential exploitation.

Importantly, this approach doesn’t provide you with just a share of the key but the complete decryption key, which lacks any identifiable markers. As a result, you remain immune from detection.

In summary, Boneh et al.’s TTE only achieved CPA security, allowing attackers to manipulate encrypted data and eventually derive the full decryption key without detection. CCA security is needed to prevent this vulnerability. And this is the subject of the next post.

Conclusion

This is the first of a two-part series on how Traceable Threshold Encryption (TTE) can address MEV challenges. We provided context on MEV, explained how TTE works, and reviewed previous research on the topic highlightning its insecurity. In the next part, we’ll dive into the latest advancements in this field.